The Making of Japanese Knives

-

Steel. Fire. Spirit. — The Soul of Japanese Knives.

Step inside the world of Sakai’s master artisans.

Witness the centuries-old techniques that transform raw steel into knives of extraordinary sharpness, beauty, and spirit—from forge welding and hardening to the final, flawless sharpening.This is more than craftsmanship. It is a living tradition.

-

Introduction — A Tradition Forged in Steel and Spirit

-

For over six centuries, the artisans of Sakai have carried forward the profound traditions of Japanese knife-making. What began as the forging of samurai swords has evolved into the creation of culinary tools admired worldwide. Yet the essence remains unchanged: to bring steel to life with fire, water, and human hands.

-

Japanese knives are not mass-produced implements, but the result of countless hours of dedication, discipline, and artistry. From forging to sharpening, every stage is infused with the artisan’s spirit. Each knife is both a functional tool and a work of art, carrying within it the heritage of generations.

-

In this journey, we will explore the four great stages of Japanese knife-making: forging (kaji), heat treatment (yaki), sharpening (togi), and handle mounting (e-tsuke). Together, they reveal how steel is transformed into a blade that chefs around the world trust as an extension of their own hands.

-

1. Forging — The Art of Bringing Steel to Life

-

Forging is the traditional art of shaping metal through hammering. In this process, soft iron and steel are heated until glowing red, becoming malleable enough to transform under the hammer’s force.

As the smith hammers the heated billet, the blade’s form begins to emerge, while its internal structure is compacted and strengthened. This results in a blade that embodies sharpness, durability, and timeless beauty.

Forging is more than a mechanical act—it is a dialogue between artisan and steel, where every strike breathes life into the metal. Each knife thus carries the spirit, skill, and experience of the craftsman who forged it.

-

1-1. Wakashitsuke (Forge Welding) — Inheriting the Spirit of the Samurai Sword

The first step in Japanese knife forging is Wakashitsuke (forge welding), where steel and soft iron are fused at high temperatures through precise hammering. Rooted in the traditions of samurai swordsmithing, this technique remains a cornerstone of Sakai’s knife-making heritage.

-

-

The process begins by heating soft iron to around 1,000°C (1,832°F), placing steel on top, and hammering the two metals together while glowing hot. The intense heat softens them just enough to fuse seamlessly, creating a laminated blade that combines hardness for sharpness and flexibility for resilience.

Temperature control is the key to sharpness. If too low, the metals will not bond; if too high, the steel deteriorates. Artisans rely on their trained eyes to read subtle changes in color, glow, and texture—timing every strike with precision.

Among the most prized materials is Yasuki steel, valued for its purity and ability to retain a razor-sharp edge. Craftsmen in Sakai often say, “A great knife begins with great materials.”

Through Wakashitsuke, the blade inherits the philosophy of the sword: harmony between strength and sharpness, flexibility and resilience.

-

1-2. Sakizuke (Preliminary Forging) — Building the “Skeleton” of the Blade

After forge welding, the process moves into Sakizuke (preliminary forging). Here, the craftsman shapes the skeleton of the knife, while further refining the steel’s grain for strength and edge retention.

Using both a mechanical spring hammer and hand hammer, the smith repeatedly heats and hammers the billet. This cycle of fire and hammering compresses the metal’s grain structure, making it finer and denser—a foundation for long-lasting sharpness.

-

Each steel type responds differently:

- White Steel (Shirogami): stretches easily, shaped in about 20 minutes for a 300mm Yanagiba.

- Blue Steel (Aogami): harder, resisting the hammer and requiring nearly double the time.

This stage is not simply shaping—it is infusing the blade with strength and character, laying the groundwork for quenching and sharpening. -

1-3. Shaping and Core Adjustment — Where the Beautiful Form Begins

Once the skeleton is established, the knife enters the shaping stage, where its elegant outline takes form. The smith cuts the han-gata (basic profile) from the forged billet—an essential step that defines all subsequent processes.

Next, the tang (the part inserted into the handle) is created, usually from softer iron for stability. Though hidden, this component is vital for the knife’s balance and durability.

-

The tip and edge are then shaped with a taper structure—thick at the base, thinning toward the edge—optimizing sharpness, comfort, and weight distribution.

At this stage, the artisan’s eye for millimeter-precise angles and thickness determines the knife’s usability. It is the design phase where functionality and beauty merge, marking the transformation of raw steel into a culinary instrument.

-

1-4. Yakinamashi (Annealing) — Giving the Metal a Moment of Rest

After forging, steel contains invisible internal stresses that can lead to warping or cracking. To relieve this tension, artisans perform Yakinamashi (annealing)—a heat treatment that gently reheats and slowly cools the steel.

This slow cooling process refines the grain structure, softens the metal for further shaping, and ensures greater sharpness and durability in the finished blade.

-

In Sakai, the steel is often cooled over a 24-hour period, giving it a moment of “rest.” Some traditional smiths still bury hot blades in straw ash, preserving carbon and producing an even finer grain.

Annealing is not just technical—it reflects the artisan’s sensitivity and patience, preparing the steel to reveal its full potential. It is a quiet yet essential step behind the outstanding reputation of Sakai knives.

2. Heat Treatment – The Soul of the Blade

-

2-1. Rough Hammering — Preparing for Precision

After forging, the blade blank may already resemble a finished knife, but in truth, this is only the beginning of refinement. Rough hammering is the essential preparatory stage that smooths the steel and readies it for heat treatment—the moment when the blade’s soul awakens.

First, a hand hammer removes the oxide scale that formed during forging. Then, a spring hammer delivers even strikes across the surface, refining the internal grain structure and evening out irregularities. This not only improves hardness, strength, and toughness, but also ensures a smoother finish that makes later sharpening more precise.

-

What looks like simple hammering is, in fact, a testament to the craftsman’s intuition and training. Each blow carries years of discipline, preparing the blade for its most transformative trial—quenching, where fire and water breathe life into steel.

-

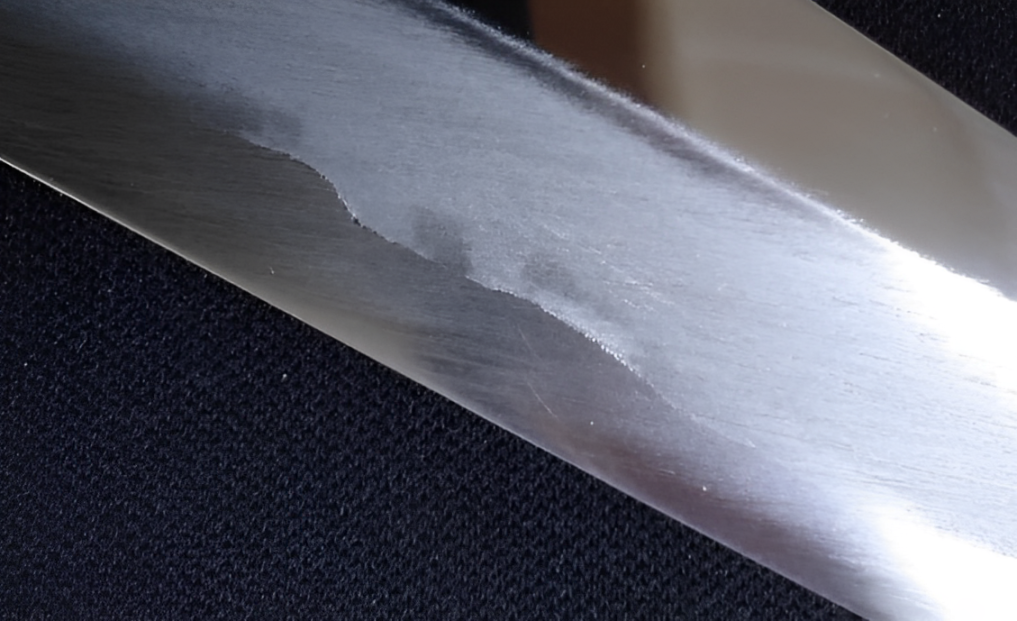

2-2. Urasuki — The Soul Embedded in the Back of the Blade

One of the most distinctive features of Japanese knives is Urasuki, a subtle concave hollow on the back of the blade. Though almost invisible, this minute adjustment dramatically improves performance.

By gently striking the blade’s backside, the craftsman reduces its contact surface with food. The result: smoother cuts, cleaner releases, and effortless slicing. For professional chefs—especially those preparing sashimi or usuzukuri—this detail is decisive.

But Urasuki is more than physics. It is the craftsman’s empathy for the chef’s hand, ensuring that every motion is fluid and efficient. In this nearly hidden hollow rests the soul of the blade—a quiet innovation born of care, foresight, and tradition.

-

2-3. Yaki-ire (Quenching)— The Balance Between Hardness and Toughness

Quenching is the most intense, suspenseful stage of knife-making. Everything depends on this single, irreversible moment.

Before heating, a special clay mixture called yakibatsuchi is applied to the blade. It prevents uneven heating, enhances cooling, and helps achieve the delicate balance of hardness and resilience. The workshop is often darkened so the smith can judge the steel’s glow with precision—a skill that takes decades to master.

-

At about 740–780°C, the blade is plunged into water. In an instant, its soft internal structure transforms into martensite, giving the steel its legendary sharpness and strength. Timing is everything: a fraction too soon or too late can mean success or ruin.

Because quenching creates immense internal stress, long and thin blades often warp. To counter this, artisans pre-bend the blade, so that after quenching it straightens perfectly—a master’s foresight at work.

- Water quenching yields maximum hardness but risks cracks.

- Oil quenching reduces damage but produces a slightly softer edge.

The choice depends on the steel and the knife’s intended character.

-

Mastery of quenching is mastery of fire itself. In Sakai, artisans still use pine charcoal and traditional bellows to maintain perfect heat distribution. Learning to read the flame’s color takes at least seven to ten years—an apprenticeship that separates novices from true masters.

Quenching is not just metallurgy. It is the soul-breathing instant when steel becomes a blade, crystallizing centuries of wisdom into one decisive act.

-

2-4. Yaki-modoshi (Tempering)— Too Much Is as Bad as Too Little

After quenching, steel becomes extremely hard—yet brittle. To prevent chipping, artisans perform tempering (yaki-modoshi), reheating the blade to restore flexibility without losing sharpness.

At around 180°C, the steel is heated and then cooled. This relieves stress, balances hardness with ductility, and ensures strength that can withstand daily use. A 330mm Yanagiba, for example, is tempered for 30 minutes at 180°C before cooling, achieving the ideal harmony.

If the temperature is too high, the blade softens too much. Too low, and it remains brittle. Here lies the craftsman’s judgment: true mastery is balance.

Tempering is a moment of calm after quenching’s violence—a deep breath that allows the steel to settle into its final state. Only through tempering does the knife gain the resilience and reliability demanded by professional chefs. The coexistence of hardness and flexibility is the very definition of Japanese sharpness.

The Soul of the Blade: The Art of Quenching & Tempering

-

Quenching and tempering are not just technical steps; they are the decisive moments that define a blade’s character.

Through rapid hardening and controlled reheating, the craftsman creates the essential balance between sharpness and toughness, giving every blade a soul that lasts a lifetime. -

Discover the Allure of Forged Knives

Forged knives embody the height of craftsmanship, where strength, durability, and beauty come together in every blade.

Subzero Treatment

At KIREAJI, steel is rapidly cooled to sub-zero temperatures, creating blades with greater hardness, durability, and edge retention. Rooted in artisan skill, this advanced process transforms steel into knives of superior sharpness and long-lasting performance.

How Cooling Transforms Steel into a Sharp Blade

A knife’s sharpness is born through cooling. This article breaks down how temperature and cooling speed transform metal at a molecular level, revealing why heat treatment is one of the most critical—and fascinating—steps in making a great knife.

Why Knives Warp: Inside the Craftsman’s Battle with Steel

Knife warping is not a flaw—it is a challenge born from metallurgy and time. This article reveals why blades warp, how craftsmen confront residual stress and metal structure, and why patience is one of the most essential tools in creating a truly stable Japanese knife.

Technical Explanation of Aike in Japanese Knives

Traditional hand-forged Japanese knives may show very small natural variations that do not appear in machine-made products.

One of the most common examples is a phenomenon known as “Aike.” Aike is not a defect, but an unavoidable result of the hand-forging process, and it does not affect sharpness, safety, or overall quality in any way.

Forged vs. Stamped: Why Hand-Hammered Japanese Knives Are the Ultimate Choice

Choosing the right bevel is only the first step. To truly understand the soul of a Japanese knife, one must look into the fire. Discover how the traditional forging process creates a "fiber flow" in steel that mass-produced stamped knives simply cannot replicate.

3. Sharpening – Revealing the Knife’s True Character

-

As the knife nears completion, the work passes from the blacksmith to the sharpener. The blacksmith shapes the blade’s skeleton through fire and hammer, but it is the sharpener’s delicate hand that defines its final form. This collaboration is a true union of artisanship, where the knife’s soul is fully awakened.

Sharpening (togi) is not just a finishing step—it determines the knife’s sharpness, beauty, and durability. Across nearly 20 stages, the blade is refined on whetstones, beginning with coarse stones and progressing to fine ones, each step revealing more of the knife’s potential.

Cold water is always used, carefully controlled in purity and temperature, to prevent heat damage or discoloration. Every detail matters, for sharpening is the moment the blade’s character is born.

-

3-1. Ara-togi (Rough Sharpening) — Laying the Foundation of Craftsmanship

Ara-togi (rough sharpening) is the first step, where the knife’s form and potential are established. Adjusting the blade’s thickness and geometry lays the structural foundation for everything that follows. It is no exaggeration to say that the future of the knife depends on this stage.

This stage has three core elements:

-

- Hasaki-suri (Grinding the Blade Tip) — Precision in Shape and Beauty

The blade is secured to a wooden base and ground on a massive whetstone nearly one meter in diameter. The edge is thinned to about 0.5 mm, forming the primary bevel. This requires both technical accuracy and aesthetic sense, balancing performance with elegance. - Men-suri (Full Surface Grinding) — Achieving Uniformity

The entire surface, from edge to spine, is ground for even thickness and weight distribution. Traditional methods may leave a kurouchi (black-forged finish), providing both rust resistance and cultural character. - Hizumi-naoshi (Distortion Correction) — Ensuring Accuracy

Any warping is corrected with wooden tools or small hammers. This delicate adjustment ensures straightness, cutting precision, and long-term durability.

- Hasaki-suri (Grinding the Blade Tip) — Precision in Shape and Beauty

-

It is said that ara-togi determines over 80% of the knife’s final character. Far beyond grinding, it embodies the sharpener’s experience, intuition, and discipline, laying the true foundation of craftsmanship.

-

3-2. Hon-togi (Main Sharpening) — Defining the Knife’s True Identity

After ara-togi, the blade undergoes Hon-togi (main sharpening), where its final sharpness and appearance are refined. Here the blade is pressed against a whetstone to flatten surfaces, adjust thickness, and hone the edge.

The two primary objectives are:

- Hiramen-togi (Flattening the Blade Surface) — correcting irregularities and achieving uniform thickness for better sharpness and performance.

- Hasaki-togi (Sharpening the Edge) — carefully honing angle, thickness, and curvature, defining the knife’s cutting feel and usability.

-

The greatest challenge is preserving the shinogi (ridge line), where the bevel meets the flat surface.

“Sharpening the shinogi is the most difficult part. I hold my breath every time I do it.” — Master craftsman

-

Every detail—angle, pressure, speed, and even moisture—must be perfectly controlled. A single mistake can ruin the knife. This stage is where the blade’s face and identity are created, demanding absolute focus and respect.

-

3-3. Ura-togi (Ura Sharpening) — The Final Step That Defines Cutting Performance

The ura (back hollow) of the blade is carefully thinned and refined in ura-togi (ura sharpening). Though nearly invisible, it directly influences sharpness and cutting efficiency.

-

By reducing friction, the blade glides effortlessly through ingredients, producing clean, precise slices. With sashimi knives, the accuracy of ura-togi determines not only sharpness but also the texture and appearance of each slice.

Even the smallest adjustment in angle or pressure can make the difference between excellence and mediocrity. Ura-togi is thus the ultimate test of finesse and sensitivity, where the craftsman’s years of training converge.

-

3-4. Shiage-togi (Final Polishing) — Unlocking the True Potential of Sakai Knives

Shiage-togi (final polishing) is the last and most delicate stage, where the knife’s ultimate sharpness and beauty emerge. This is often described as the moment when the craftsman “breathes soul into the knife.”

Each blade is polished individually, with careful selection of whetstones—progressing from coarse, to medium, to fine. Through this gradual process, the knife attains both a razor-sharp edge and mirror-like finish.

This is not only technical work but a discipline of focus, patience, and devotion. Sometimes a single knife requires hours of polishing, every movement intentional, every detail considered.

At this stage, the knife transcends being a tool—it becomes a partner for the chef, reflecting their skill and amplifying their artistry.

And yet, the journey is not over. The blade now awaits its final union with the handle—only then is the Japanese knife truly complete.

4. E-tsuke (Handle Mounting) — Where Function Meets Comfort

-

After the blade is finished, the process moves to its crucial final stage: E-tsuke (handle mounting). Here, the knife transforms from a finely crafted blade into a complete instrument—not just a tool, but a true partner for the chef. Only when the handle rests naturally in the user’s hand does the knife truly come to life.

-

Selecting the Wood — Ho-no-ki (Magnolia) or Rosewood?

Two types of wood are most commonly used for handles. Ho-no-ki (magnolia) is lightweight, absorbs little water, and has a smooth, gentle feel—making it a favorite of professional chefs. In contrast, rosewood and other hardwoods such as padauk are valued for their durability and elegant appearance.

Choosing the right wood is more than an aesthetic decision. It greatly influences the tactile experience and comfort of the knife in daily use.

-

The Method of Attachment — The Art of Heating and Tapping

In this process, the nakago (tang)—the metal portion at the base of the blade—is heated and carefully inserted into the handle with a wooden mallet. As the tang cools, it contracts, locking itself securely in place.

This skilled step requires absolute precision—even the slightest misalignment can disrupt the balance of the entire knife. Afterward, the craftsman checks and corrects any distortion to ensure perfect straightness.

Between blade and handle sits the kuchiwa (collar), often made of water buffalo horn in high-end knives. It adds durability while providing a graceful transition between steel and wood.

-

-

-

Why It Feels Right — A Fusion of Skill and Design

Historically, every handle was made entirely by hand, limiting output to around 100 pieces per day. Today, modern tools allow greater production, yet each step—wood selection, natural drying, shaping, drilling, beveling, and collar fitting—is still entrusted to skilled artisans.

Special attention is given to how the handle feels: edges are rounded for comfort, surfaces are shaped for a firm yet natural grip, ensuring a handle that is secure, slip-resistant, and fatigue-reducing.

The handle is not merely an accessory—it is the counterpart to the blade, balancing functionality and aesthetics in equal measure.

-

The Final Step to Completion

Only when the finely sharpened blade and the perfectly mounted handle come together does the knife reach its true completion. In the chef’s hand, the knife becomes an extension of the body, a tool for expression through ingredients.

This union of steel and wood—shaped by tradition, refined by innovation, and perfected through craftsmanship—is the reason Sakai knives are cherished by chefs around the world.

Conclusion — Where Steel, Wood, and Spirit Become One

-

A Japanese knife is far more than steel honed to sharpness. It is a harmony of elements—metal, wood, water, fire, and above all, the artisan’s heart. From the fierce heat of the forge to the quiet patience of final polishing, every process reflects a dialogue between human skill and natural materials.

-

When blade and handle are finally joined, the knife reaches completion—not as a mere cutting tool, but as a partner in the hands of a chef. With each slice, it carries forward the wisdom of centuries, preserving aroma, texture, and beauty in the ingredients it touches.

-

This is why Sakai knives are beloved across the world. They embody the Japanese philosophy that true mastery lies in balance: strength and flexibility, tradition and innovation, utility and beauty.

-

In every cut, one can feel the legacy of six hundred years—the living soul of Japanese craftsmanship.

The Process of Making Japanese Knives

Video Provided: ProcessX (YouTube)

See how a Sakai knife is born—

forged in fire, tempered in water, sharpened to perfection, and completed with a handcrafted handle.

Ⅰ. Why Is the Manufacturing Process So Important?

-

Simply put, the manufacturing process defines a knife’s true performance.

Think of cooking: having premium ingredients alone doesn’t guarantee a delicious dish. It takes proper preparation, precise techniques, and the right balance of seasoning to create a meal that truly shines. The same principle applies to knives.

-

Key Factors that Shape Knife Quality

-

The diagram shows how different stages—steel selection, forging & heat treatment, edge finishing, and handle attachment—directly influence performance attributes such as sharpness, durability, balance, and comfort.

-

Even with the finest steel, poor heat treatment can reduce durability, careless edge finishing can dull the blade, and improper handle attachment can compromise comfort and balance.

-

Just as a poorly executed dish may still be edible but lack depth and refinement, a knife made without precision in each stage may still cut—but it will not perform at its best over time.

-

This is why the precision of the manufacturing process ultimately determines the true quality of a Japanese knife.

-

The True Formula of Quality: What Really Makes a Knife Exceptional

-

A knife becomes exceptional not by material alone but by the harmony of the steel that defines its potential, the forging that builds its core strength, the edge finishing that unlocks peak sharpness, and the handle attachment that shapes balance and feel.

When these elements work together with mastery, the blade achieves its full performance and lasting character.

Ⅱ. Japanese Knife Culture — The Harmony of Tradition and Innovation

-

Material Innovation and the Modern Era

Japanese knife-making has evolved over centuries, constantly adapting to the needs of each era. Early knives were crafted from hagane (carbon steel)—sharp but prone to rust. The introduction of stainless steel in the early 20th century revolutionized the craft, making knives more durable, easier to maintain, and ideal for everyday use. As a result, Japanese knives became essential tools, treasured not only by professional chefs but also in home kitchens around the world.

-

The Fusion of Innovation and Tradition

Innovation in Japanese knife-making goes beyond materials. In the late Edo period (1603–1868), production processes became specialized—craftsmen focused exclusively on forging, sharpening, or handle making. This division of labor enabled greater precision and artistry, resulting in knives that were both highly functional and visually stunning.

-

The modernization continued into the Meiji era (1868–1912), with tools like spring hammers speeding up forging. By the Taishō era (1912–1926), powered grinding wheels and buffing systems had entered the sharpening process. These technological improvements reduced physical strain on artisans while preserving the soulful craftsmanship, blending tradition with efficiency in perfect harmony.

-

Preservation of Craftsmanship

Despite technological advances, authentic Japanese knives still carry the spirit of handcraft. Skilled artisans continue to forge, shape, and polish each blade—infusing it with patience, precision, and the artistry passed down through generations. The result: every knife is a living testament to skill, passion, and cultural heritage, enchanting chefs and knife enthusiasts around the world.

-

A Future Shaped by Tradition and Innovation

Japanese knives are more than just tools—they are embodiments of a seamless blend between tradition and progress. Refined over centuries, they have become cultural icons connecting us through the art of cooking.

Whether in a Michelin-starred restaurant or a cozy home kitchen, a Japanese knife offers a unique experience: the precision of the past, fused with the innovation of the future. Each blade carries a story of resilience, mastery, and the timeless beauty of Japanese culture.

-

The Soul of the Blade: How Japanese Knives Fuse Tradition and Innovation

-

Pair text with an image to focus on your chosen product, collection, or blog post. Add details on availability, style, or even provide a review.

The Soul of Craftsmanship

-

Quenching: The Moment Where Steel Gains Its Soul

Quenching is one of the most decisive moments in the life of a blade. Heating steel in fire, then cooling it in an instant, determines its sharpness, durability, and spirit. A single breath of carelessness can alter the outcome, which is why even the most experienced artisans face this step with unshakable tension.

-

It is not simply a technical procedure. Quenching demands intuition, focus, and humility before the material. The steel itself reveals subtle signs—its glow, its sound, the way it shifts in the fire. To read these signs and act at the exact right moment is an art that no book can teach, only years of lived experience.

-

No two attempts are ever the same. Each piece requires absolute commitment, because the margin between perfection and failure is as thin as the blade itself. Yet it is precisely this challenge that gives quenching its profound weight.

-

When someone grips a finely sharpened tool—when they feel its precision, trust it in their work, and treasure it for years—that is the moment we artisans are rewarded. It reminds us why we pour our hearts into every single piece: to create something that carries both strength and soul.

-

Quenching is where craftsmanship is most honestly tested. And it is here, in this fleeting moment of fire and water, that the blade’s true life begins.

Experience the sharpness trusted by 98% of Japan’s top chefs — handcrafted in Sakai City.

Through our exclusive partnership with Shiroyama Knife Workshop, we deliver exceptional Sakai knives worldwide. Each knife comes with free Honbazuke sharpening and a hand-crafted magnolia saya, with optional after-sales services for lasting confidence.

KIREAJI's Three Promises to You

-

1. Forged in the Legacy of Sakai

From Sakai City—Japan’s renowned birthplace of professional kitchen knives—each blade is crafted by master artisans with over six centuries of tradition. Perfectly balanced, enduringly sharp, and exquisitely finished, every cut carries the soul of true craftsmanship.

-

2. Thoughtful Care for Everyday Use

Every knife includes a hand-fitted magnolia saya for safe storage. Upon request, we offer a complimentary Honbazuke final hand sharpening—giving you a precise, ready-to-use edge from day one.

-

3. A Partnership for a Lifetime

A KIREAJI knife is more than a tool—it is a lifelong companion. With our bespoke paid aftercare services, we preserve its edge and beauty, ensuring it remains as precise and dependable as the day it first met your hand.